Who are the people of the Pacific? Pacific people live in the biggest ocean in the world: the Pacific Ocean. They are custodians of the sea, ocean traversed and are community and village-made. Embedded with their cultural systems, strong values, traditions, and spirituality (Statistics NZ, 2018).

How has this region been defined? Oceania is a region made up of thousands of islands throughout the Central and South Pacific (National Geographic, 2023).

Pacific people have never been involved in these conversations and these terms have been imposed on us.

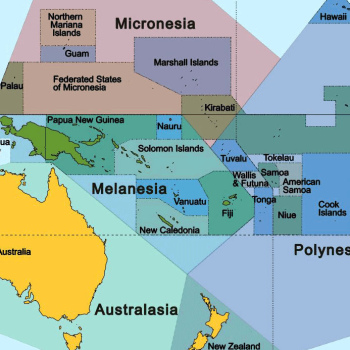

The Pacific has been divided into three regions, although these terms are outdated and originated from racial characteristics from Jules Sebastien César Dumond d’Urville, a French explorer in 1820. He divided them into three broad categories of Polynesia, Melanesia, and Micronesia.

- Polynesia (Poly means many and nesos means island),

- Melanesia (Melas means black),

- and lastly, Micronesia (Micro/mikros means small).

A product of racial theory, but after over 200 years these terms are still being used today and there have been no alternatives developed (Kundra, 2018).

These blanket terms have been used to simplify and box our complex society. Pacific people have never been involved in these conversations and these terms have been imposed on us.

“It is the water that connects the people of the Pacific.”

But how do Pacific people define where they come from? Examples of how Pacific poets and academics portray where Pacific people come from: “It is the water that connects the people of the Pacific.” (Professor Epeli Hau’ofa) “We sweat and cry salt water, so we know the ocean is really in our blood.” (Teresia Teaiwa) “[...] trans-Moana people because the commonalities are strong and embedded in pre-European history.” (Steven Ratuva) “The ocean is not a metaphor; the ocean is home. It returns us to the Pacific when we lose ourselves in the bindings of the nation-state. It teaches us that our smallness is real, even when our connections are vast.” (Sam Iti Prendergast)

“We are the sea; we are the ocean. Oceania is us.”

When Pacific people look at maps, they can’t see themselves.

On a map, our islands are a speck in the ocean –invisible– their identification dependent on which colonial power you are looking from. We are shown to be lost in a vast ocean, with names that were forced on us by colonial explorers.

A quote from Professor Epeli Hau'ofa: “We should not be defined by the smallness of our islands but in the greatness of our oceans. We are the sea; we are the ocean. Oceania is us.”

Tonga was known as the ‘Friendly Islands’: “Cook called the Tonga islands the Friendly Islands because the native inhabitants provided him with necessary supplies and gave him a warm welcome.” (Britannica , 2024)

Other examples are:

| Indigenous name | Previously known/or colonial name |

|---|---|

| Hawai'i | Sandwich Islands |

| Kiribati | Gilbert Islands |

| Tuvalu | Ellis Islands |

| Vanuatu | New Hebrides |

| Tahiti | Society Islands |

| ‘Uvea mo Futuna | Wallis and Futuna |

| Niue | Savage Island |

| Nauru | Pleasant Island |

| Sāmoa | German Sāmoa/Western Sāmoa |

Cook Islands was named after James Cook, by Russian cartographer Admiral Adam Johann von Krusenstern. Even though Cook and his crew only set foot on the islands once to restock supplies. The Cook Islands have had two national referendums to propose a new name for the country one in 1993 and one in 2019, but an indigenous name has yet to be decided.

The view of the Pacific is very different depending on political relationships and political climate at the time.

Let's talk about Pacific Identity and how others see us. Depending on where you are placed in the world. The view of the Pacific is very different depending on political relationships and political climate at the time.

- Australia’s perception focuses on the countries and islands they support and have relationships with – Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Fiji (Melanesia)

- New Zealand’s position in the Pacific – Cook Islands, Tokelau, Niue, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, (Polynesia)

- United States: Hawaii, Guam, Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas (Northern Pacific and Micronesia)

These places are often invisible or unheard of to other parts of the world if you don’t have any political associations with these islands.

See the interactive graphic “Colonial control in the South Pacific at Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand”: https://teara.govt.nz/en/interactive/24236/colonial-control-in-the-south-pacific

We are at risk of losing Pacific languages, cultures, and traditions if we don’t use them.

But how should we define the Pacific? By their Islands and their ethnicity. We need to respect that many islands are still fighting for independence and to reclaim their indigenous names.

We are at risk of losing Pacific languages, cultures, and traditions if we don’t use them. Our homes are at risk due to sea level rise, we need to ensure indigenous cultures in the Pacific are being practiced and preserved.

Being Pacific in the 1800s and 1900s is different from being Pacific in 2024, but racial theories are still being used today. How can Pacific people be involved in correcting history? Our country, our Islands, our villages’ names have been changed, our beautiful ancestral names are shortened so others can pronounce them without having to make an effort. But little do they know that these names hold strength, our family history, our connections, our stories, our culture, and traditions. By regaining our names, we will regain our voice. Nothing is about us, without us.

Works Cited

- Britannica. (2024, March 11). History of Tonga . Retrieved from Britannica : https://www.britannica.com/place/Tonga/History

- National Geographic (2023, November 10). Australia and Oceania: Physical Geography. Retrieved from National Geographic : https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/oceania-physical-geography/

- Hau'ofa, E. (1994). Our sea of islands . The Contemporary Pacific.

- Kundra, D. S. (2018, September). Historical Mysteries: Does Tripartite Division of Pacific Islands Exist? (I. Times, Interviewer)

- M, M. (2019, March 11). These islands in the Pacific Ocean have changed their names. Retrieved from Sharing Information: https://mshrf.wordpress.com/2019/03/11/these-islands-in-the-pacific-ocean-have-changed-their-names/

- Prendergast, S. I. (2023, July 16 ). E-Tangata. Retrieved from E-Tangata.co.nz: https://e-tangata.co.nz/nzoa-pijf/making-a-life-on-unceded-indigenous-land/

- Ratuva, S. (2020, August 30). Decolonising our ‘differences’. (D. Husband, Interviewer)

- Teaiwa, T. (2017). “We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.”. International Feminist Journal of Politics.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, March 11). Oceania. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Oceania-region-Pacific-Ocean

- Statistics New Zealand (2018). Pacific Peoples ethnic group.https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-ethnic-group¬ summaries/pacific-people

- Bertram, G. 'South Pacific economic relations - Pacific neighbours', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/interactive/24236/colonial-control-in-the-south-pacific (accessed 17 March 2024)