Why does freshwater monitoring matter?

The Vaisigano Citizen Science Project

How much do we know about the Vaisigano river? Though the textbooks say it is the largest river running through the Pacific Islands, Samoans say it is the longest. Either way rivers show us a reflection of who we are, so studying and monitoring the freshwater ecosystem can tell us about its health, its habitat and its relationship to Samoans.

The Vaisigano citizen science project is a collaboration between the Übersee-Museum Bremen and the National University of Samoa to examine the river together. The illustrated story takes a deep dive into this project and why monitoring the river matters.

Do you see it?

Come closer. Have another look

There it is. As always. Meandering and traversing through Upolu, the island in Samoa.

Vaisigano has always been a part of Samoa. Sometimes a deluge, sometimes a trickle.

But how much do we know about this river? Textbooks call it the largest, Samoans call it the longest.

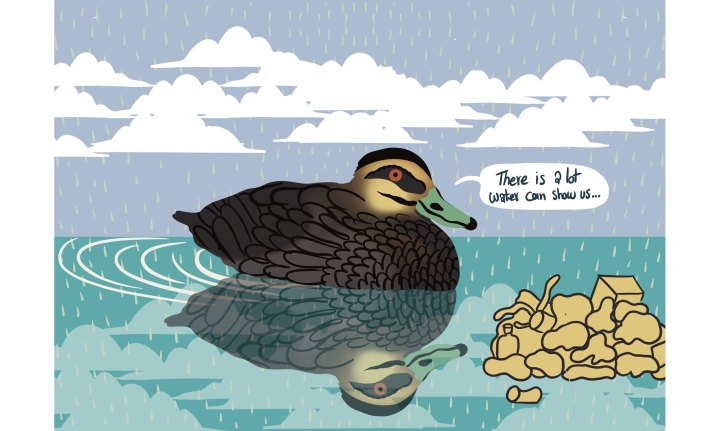

But have you ever stepped closer and had a look? There's a lot water can show us... Not just a reflection of who we are

But a glimpse into more. Rivers give, of course. But they also receive. They bear the brunt of human action. Sometimes swelling with unseasonal rainfall, sometimes choking with discharge and debris.

In some parts of Europe, there have been developments on ways to study water quality. The Saprobic Index, in particular, pays attention to the type and quantity of organisms in the water.

Think of it this way, researching citizens and the people of a country can reveal how a nation is functioning or performing. Similarly, studying the constituents and organisms in water can tell us about the health of a river. How much has organic pollution affected her?

And what would this scientific practice look like in the Pacific islands? In partnership with the National University of Samoa, the Citizen Science Vaisigano project explores exactly this.

It's true science is all about facts. Evidence. Rationale.

But science is also about emotions. Wonder. Curiosity.

The team couldn't study the health of Vaisigano without first understanding what relationship Samoans share with it. So the team began by asking the student volunteers to decode the river through observation and artistic interpretation.

Then came scientific mapping. In order to study the health of a river ecosystem, the team would need baseline data on the habitat, water chemistry and fauna. By making it a citizen project, we hoped to not only ensure regular data collection but also educate young people on freshwater ecosystems.

This is one example of what it looks like in action: Measuring a stretch of the river and then seeing how long it takes a leaf to go down this stretch.

Done multiple times, this simple experiment can teach us a few things. How steep is the gradient of the river? What is the volume of the water? Is there friction between the bed of the river and the water? What shape does the river channel have?

The team also tried to capture data on the biological communities that are a part of the river. This meant catching different insects and organisms from different parts of the river: Slow moving sections, fast moving ones, under rocks and plants, and so on.

Aquatic organisms can only survive if certain conditions are met. So studying them can indirectly tell us about water quality and the health of the river.

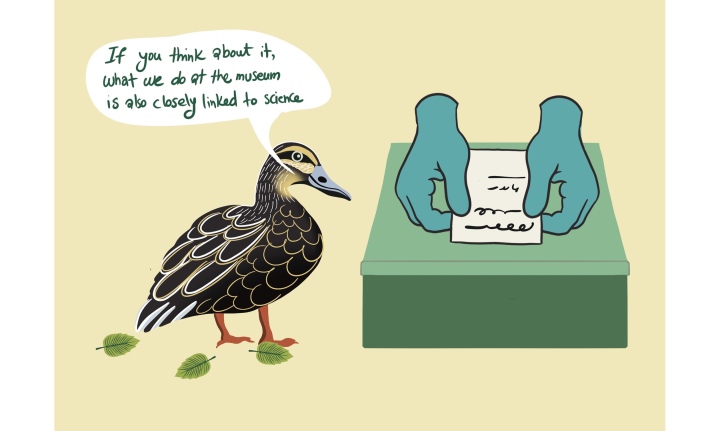

Michael Stiller, head of department of Natural History at the Übersee-Museum, then led the process of sorting and labelling the specimens.

If you think about it, what a museum does is closely linked to science. There is a systematic method to documenting, digitising and preserving knowledge.

Museums don’t just house relics of the past. By actively engaging in the present, we also capture a glimpse of what the future could be.

Do we know yet what it will be, what the future of Vaisigano is?

No, but this is only the beginning

Scientific endeavors take time. But it doesn’t mean it is going nowhere. The results and answers will come. Surely, steadily.

Which means: We have to keep observing, keep engaging, keep collecting and studying data.

We have to keep our efforts going …

… And make sure to not stop the flow.

This story relates to the topics Collecting, Cooperation, Samoa, Vaisigano Citizen Science, . Discover more content on these topics by clicking one of the tags!