Call me by my name

The Samoan ie toga is more than just any ordinary mat or Matte as it is sometimes referred. It is a product of skill, love, talent, dedication and is highly regarded in Samoan culture. Yet the museum world can be very limited in capturing the full scope of its meaning and functions. In this illustrated story, we uncover layers of meaning and the effect of objects reduced to standardised terminology.

What do you see here?

It’s tough to miss the obvious. The woven pattern. The wheat-coloured material. The loose fringe.

Our first instinct, of course, was to call it a mat. Or to be specific, Matte. But to do so would be painting just half the picture.

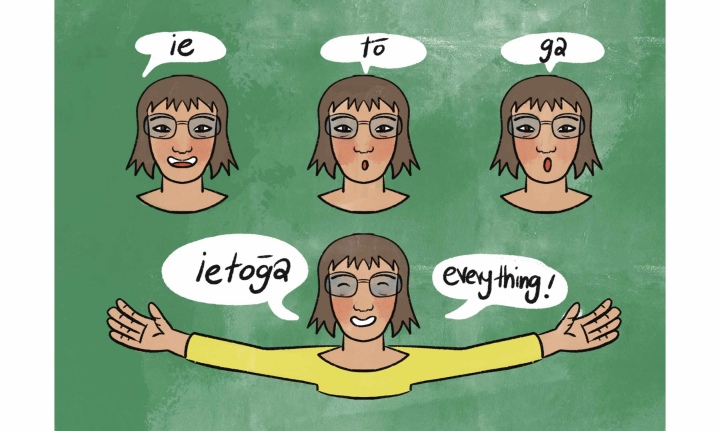

Because what we actually called a Matte is a Samoan ie tōga. Much more than a mat. No less than a cultural practice.

So, what’s in a name?

Everything.

Think of a mat and the function that immediately comes to mind: A place to sit, a covering for the floor, a greeting point for dirty, muddy shoes. The opposite of respect. The opposite of reverence.

This ie tōga, on the other hand, is never used as a sitting mat. Every weave is a product of skill, patience, talent, love, dedication and utmost regard for Samoan culture.

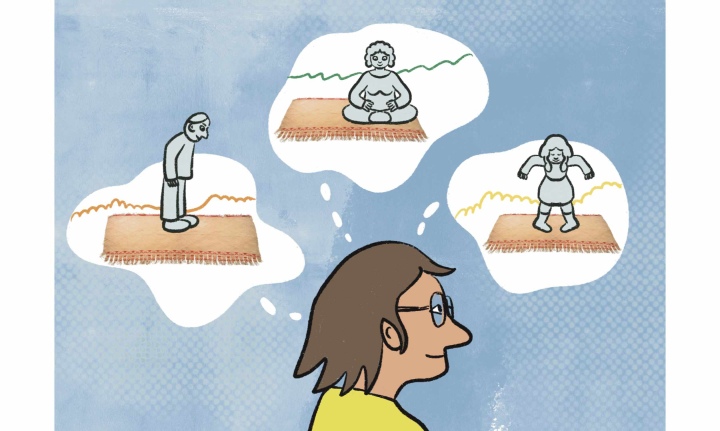

An ie tōga isn’t just a labour of love. It is also a marker of love. It is associated with special occasions. Think weddings, funerals, the blessing of a newly-established house or church.

If mats are a stepping stone at a doorway, ie tōgas are bridges, connecting people. In 2002, an ie tōga was gifted to New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark. This gesture was made after her public apology to the Samoan people for everything that happened during the time Samoa was administered by New Zealand from 1914 to 1962. This is just one story. Every type of mat in Samoan culture has a rich history and a deserving name.

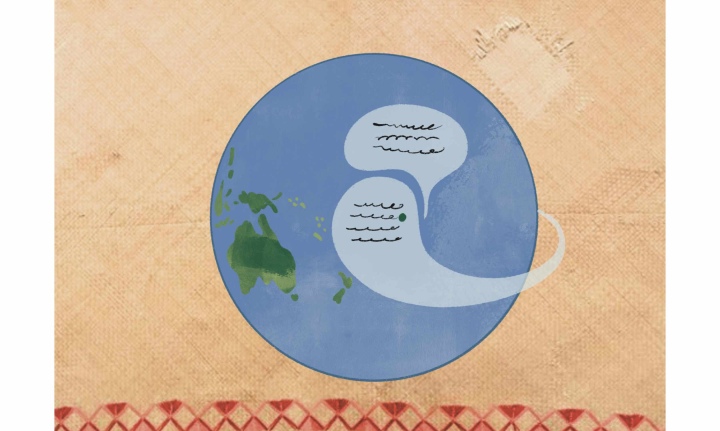

And herein lies the conundrum. As a museum, we are privy to the knowledge and history behind each of these mats. But we are limited by language.

What is the German or English equivalent to these rightful names? How do we make our collections accessible to people across cultures, without reducing the legitimacy or legacy of the artefacts?

Sometimes, as people involved in documentation and knowledge management, we are sure that there must be a right way. The right word, the right vocabulary or the right description of something. But there is no end to this search.

“Through this project I realised that there exists this online portal digitalpasifik.org, one that allows Pacific Islanders to explore digital versions of their cultural heritage, housed in collections overseas. For this, you would need completely different vocabulary for someone to find your collection. So perhaps, it is more important to know where exactly something comes from.” (team member, Übersee-Museum Bremen).

Simply put, a native might not search for a “mat” on such a portal, and without knowing better, museums might not use the accurate terms to describe their collection.

We can’t claim to have it all figured out. But what we have learned, in our collaboration with our Samoan partners, is that dialogue, and mutual willingness to have this dialogue, can go a long way.

What did that look like in our case?

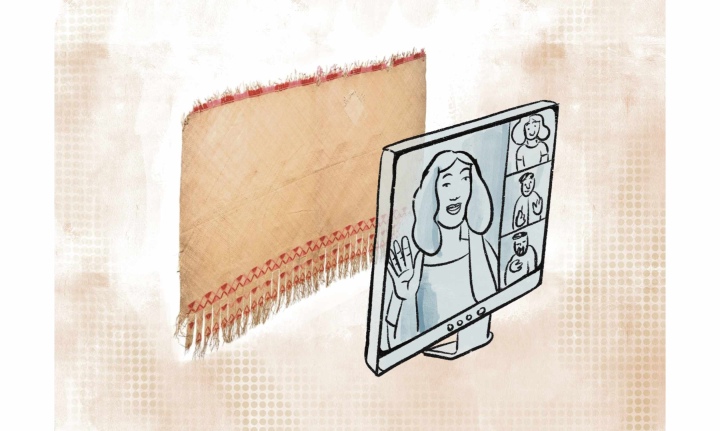

Among many things, a video call where we gave our partners from the National University of Samoa a tour of our storage room within the museum. Women mat weavers from Samoa were also part of the meeting.

Before the meeting, the objects were laid out by the conservators and strategies to move across the room smoothly were mapped out.

During the meeting, we zoomed in on the details - the weave of the mat, the texture, the fringe ends. We asked questions, and we received a world of stories, perspectives and nuances about the mats, their makers, and the meaning in their making.

We may not have been physically together in the same room but it’s incredible how knowledge was shared, exchanged and refined.

So, do we use ‘mat’? ‘Matte’? What’s in a name, you ask?

“As a museum, we are still learning. And unlearning. But one thing we do know: As documentors of knowledge, we need to ask questions, not assume. Listen, not lead.” (team member Übersee-Museum Bremen)

As the popular saying goes, nothing worth having comes easy. Especially not museum collections woven together with respect, trust and mutual collaboration. But that’s what makes it all that more priceless, and worth preserving.

This story relates to the topics Museum Work, Samoa, Metadata, . Discover more content on these topics by clicking one of the tags!